For vocabulary instruction to be useful, it must supply students with the words they truly need.

We want students to have robust vocabularies so that they can comprehend what they’re reading, have a well-stocked toolbox for writing, and understand the wordplay they encounter in puns and figurative language.

The words we teach them must help them do these things.

Which words do that?

That’s the question, isn’t it?

The answer is really long, but it’s worth finding out.

My best friend (a therapist) told me once that our theory guides our interventions.

If our interventions aren’t working, it’s likely that our theory is wrong.

That’s why it’s worth our time to learn the theory behind what we do, and that’s true of choosing the vocabulary words to teach.

? Which Words Do We Teach?

The framework I follow was developed by Beck, McKeown, & Omanson in the book, The Nature of Vocabulary Acquisition.1

They say that there are three tiers of words that form our vocabularies.

? Tier One Words

Tier One words are the everyday words.

These are words that we don’t have to teach the meanings of (although in early grades we will teach the spelling of them).

These are words like happy, sad, sun, horse, house, fork, or dinner.

We don’t need to teach the meanings of these words because students will encounter these words over and over in their daily lives.

Do they need these words? Yes.

Do we need to actively teach the meanings of these words? No.

Even if these words are bolded in your textbook or highlighted in your teacher’s edition, you don’t need to include them in formal vocabulary instruction.

You may want to do a quick check for understanding, but there’s no need to add them into a full instruction protocol.

How can you tell if the word is a Tier One word?

One simple test is to think if it’s a word that might be in a baby’s board book.

If so, it’s probably a Tier One word.

Let’s look at the tiers we do need to teach.

? Tier Two Words

They are the useful words found across a wide variety of content areas.

The words that form the core of most early elementary teachers’ vocabulary instruction and all ELA teachers’ vocabulary instruction are Tier Two words.

They are the words that we need to know to read well and comprehend well.

These are words that are not content-area specific, but are used by those with good language skills.

My favorite Tier Two word? Egregious.

Tier Two words include words like significant, evaluate, intimidate, pertinent, alleviate, and niche.

I could list Tier Two words all day!

Tier Two words get more sophisticated as the grade levels increase, but they don’t stay in the grade level they’re taught.

We assume that the second-grader who was taught cooperation will remember that and be able to use it effectively in third grade and fifth grade and twelfth grade.

Beck, McKeown, & Kucan say that these are words that students will read in text, but not hear in conversation.

Because of this, if they’re not explicitly taught, students are unlikely to truly learn them.

Why should we teach them?

Beck, McKeown, & Kucan say, “Because of the large role Tier Two words play in a language user’s repertoire, rich knowledge of words in the second tier can have a powerful impact on verbal functioning.”3

? Tier Three Words

Tier Three is the most sophisticated level of words.

They’re less common words that are often connected to a certain content area.

If you use the Depth and Complexity framework, these words are the Language of the Discipline.

If you teach science or social studies, you’ll have vast numbers of Tier Three words.

Math has loads of them as well.

In language arts, there is a limited number of Tier Three words.

Students use these across multiple grade levels, mostly consisting of literary elements, genres, and types of writing.

These words are necessary to be mastered, and they have to be taught with intention.

Without an understanding of them, students are unable to demonstrate content mastery.

For decades, we’ve known that many of the difficulties students experience in mathematics are language issues.

As early as 1960, studies were showing that the specialized language of mathematics poses a problem for students.

It’s almost like a foreign language, with students translating English statements into math statements before they can solve the problem.2

Tier Three words definitely deserve and need to be taught.

? To recap:

Early elementary and ELA teachers of all levels will primarily teach Tier Two words.

Upper elementary teachers (especially those who are departmentalized) and secondary teachers will primarily teach Tier Three words.

How many is reasonable?

It will come as no surprise that researchers have an opinion on this.

The most commonly cited study is the one that was done in 1984 by William Nagy and Richard Anderson called, “How Many Words Are There in Printed School English?”4

They looked at the printed words students in grades 3 – 9 would encounter, and they found that there are about 88,500 of them.

They did a later study in 1992 that found that if you included proper nouns, the multiple meanings of words (“down” as in duck feathers and “down” as in direction), and idioms, there would be 180,000 word families.

Friends, we can’t teach 88,500 words!

What an even later study by Nagy & Herman found was that you can estimate vocabulary by grade level.

- Third graders’ vocabularies average about 10,000 words

- Twelfth graders’ vocabularies average about 40,000 words

That means that students need to learn about 3,000 words per year.

If you take out the Tier One words, we probably have about 7,000 words we need to teach.

That still sounds like a lot, but if we divide that out over the years, it’s manageable.

If you call 400 or so words a year manageable.

I do.

You know why? Once you know how to do it, this amount is absolutely doable.

That’s what Vocabulary Luau is all about.

My goal is to help you do this in a way that makes sense in real classrooms.

? How to Decide Which Are the Most Important Words to Teach?

There are several methods for figuring this out.

A lot of the methods are based on frequency: how often do those words show up in use?

That sounds great, but I agree with Beck, McKeown, & Kucan that this is flawed because words can be frequent but easy or frequent but not really useful.

The example they use is that the word breaking would be chosen in a frequency list, but it’s really a form of break, which is a Tier One word.

In their book Teaching Word Meanings, Steven Stahl and William Nagy suggest adding in more criteria:5

- Utility (usefulness – no need to teach sesquipedalian)

- Requirement for learning (needed to understand and apply content)

I think these are important to consider, so let’s pause here and look at what we’ve got so far.

We need to be teaching words that occur often enough that they’re worth learning, are useful to students but unlikely to be used in speech commonly, and are necessary to truly master content.

There’s one more idea from Beck, McKeown, & Kucan: conceptual understanding.

By this they mean words that students might understand the concept of but not know a word to describe it.

For example, a student may understand the idea of something’s being hard, but not knowing other words for it like difficult, challenging, arduous, grueling, or onerous.

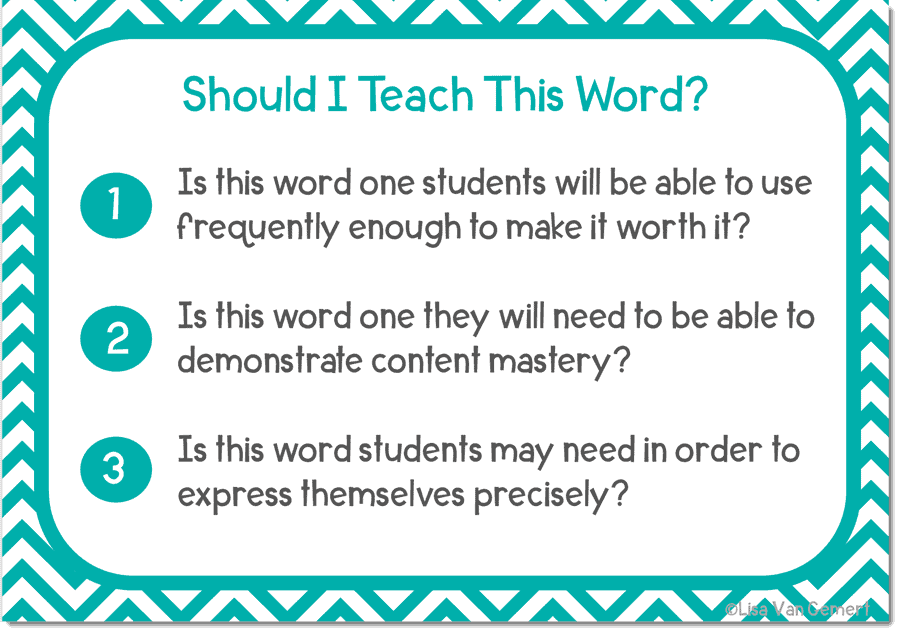

There are many other ideas about how to choose words, but after reading (a lot) about what a bunch of researchers have to say about it, but in my opinion (!), the best way for a teacher to choose words to teach is to consider these things when looking at which words to teach:

- Is this word one students will be able to use frequently enough to make it worth it?

- Is this word one they will need to be able to demonstrate content mastery?

- Is this word students may need in order to express themselves precisely?

I’ve made a simple index-card sized printable of these questions that you can keep handy.

Print it out in color or black and white (there are a few versions).

You can keep it with your lesson planning materials or tape it to your computer monitor (like me!).

? Where Do You Find Those Words?

So now you know what questions to ask when you encounter a word and need to decide if it’s worth teaching.

The next question is, “Where do you find the words to evaluate in the first place?”

Look in the Standards

Virtually all standards include vocabulary. Much of this belongs in Tier Three because it’s specific to the discipline.

For example, if you look up the Common Core State Standards in math, you’ll find lots of very mathy words that students are supposed to know.

They are almost all specific to math – words like integer and probability.

However, there are some words in the standards that belong in Tier Two. For instance, congruent and fraction have uses outside of math as well.

If you’re teaching that specific content, teach those specific words, no matter if they are in Tier Two or Tier Three.

Let’s take the word integer and hold it up to the questions we are demanding of words in order to justify teaching them:

- Is this word one students will be able to use frequently enough to make it worth it?

Absolutely! Integers are integral (See what I did there?) in math instruction for many years.

- Is this word one they will need to be able to demonstrate content mastery?

Again, students will not be able to answer many questions put to them if they don’t have a strong understanding of what we mean by the word.

Even a very cursory look at a math textbook will show dozens of problems that require students to understand the word.

- Is this word students may need in order to express themselves precisely?

Yes. If students have to say, “You know, the words on the number line that are positive and negative whole numbers” instead of integers, they will struggle.

Some standards vocabulary words are a form of Tier One words.

What I mean by that is that they are definitely need-to-know words, but we use them so often in speech and instruction that they don’t necessarily need to be explicitly taught.

You can leave those out.

If you’re teaching third grade or higher, you also need to consider if the word was taught earlier (so a pre-test may be needed).

Some standards words need to be taught because the students know them in a different context, and that can lead to confusion.

For example, the word conductor is a science word in the NGSS, but a lot of students will come to school familiar with the word as it relates to the person driving the train!

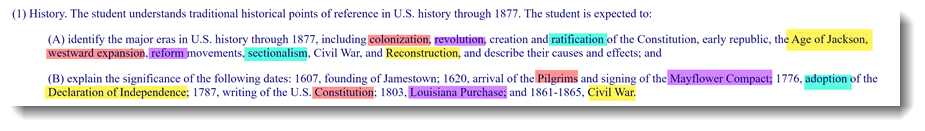

Take a Closer Look at Your Standards

While the standards sometimes specifically list the vocabulary words that they want students to know, it’s worth reading through the standards with an eye to embedded vocabulary.

Let’s look at the 8th grade social studies standards in my state (Texas).

I took a little snippet of it here:

I highlighted the vocabulary words in this little section.

Now, would I need to teach all of these? No. For instance, they’re going to get “Civil War” in instruction about the Civil War.

Run these words through the questions above.

And some of you may need to add in a fourth question: Will this word be tested?

For that question, keep in mind that dates and people are also vocabulary.

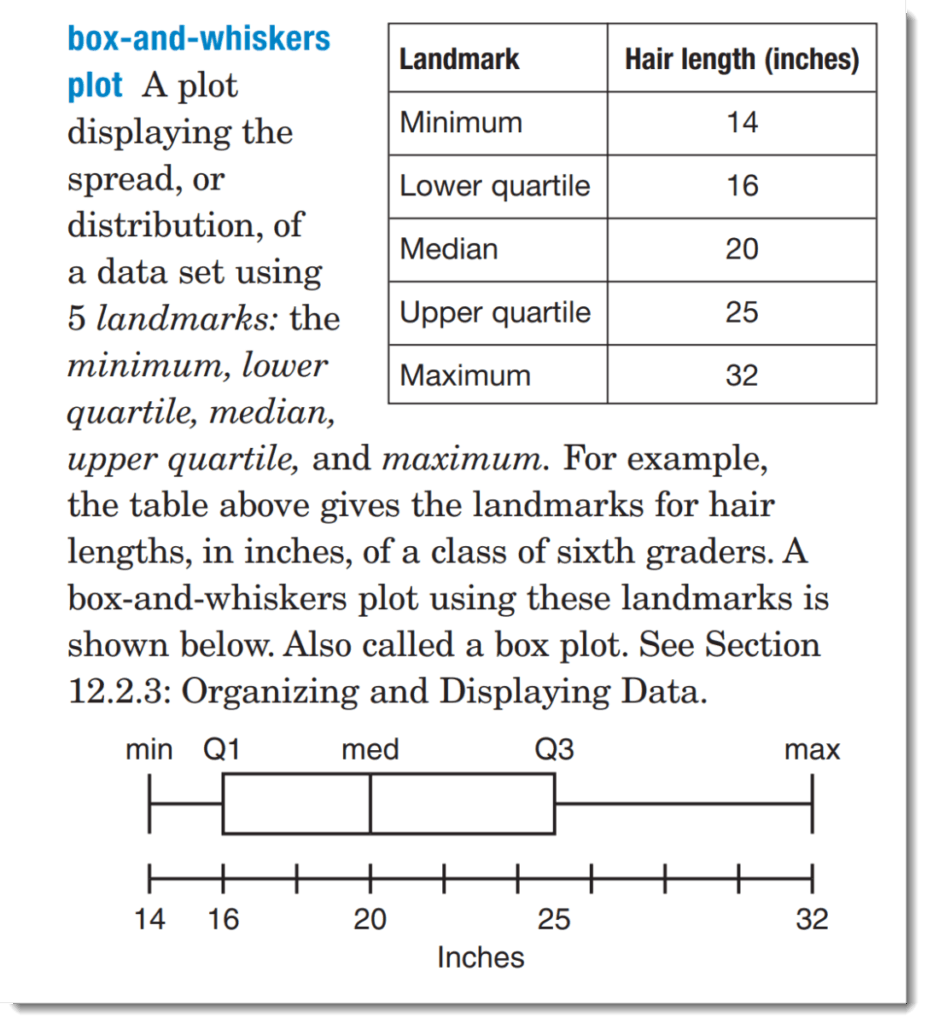

I grabbed a screenshot of the glossary of the Everyday Math textbook published by McGraw-Hill.

Every word in the glossary deserves at least a glance.

If you know they already know it and know it well, or if you know that you already have it earmarked to teach, skip it.

If you don’t know those two things about it, run it through the three questions.

- Is this word one students will be able to use frequently enough to make it worth it?

- Is this word one they will need to be able to demonstrate content mastery?

- Is this word students may need in order to express themselves precisely?

(Remember that you can get the simple index-card sized printable of these questions that you can keep handy.)

When I look at a glossary like this, I pay special attention to a few things.

Long entries – Long entries are a sign that the word is worth careful consideration. It costs money to print those pages, so they don’t waste space. If they took a quarter of a page on a term, it’s likely that it has strong value.

Entries with graphics – One of the greatest curriculum shifts we’ve seen is to graphics and images being as important as the text for learning.

We’re seeing more and more of it on assessments, too. If graphics or diagrams are included in the glossary, I look closely at that word.

References to other entries – If the glossary entry refers to another entry, ask yourself if you need to teach one or both of them. Are they terms that are truly interchangeable or variants (bisect and bisector)? Do both need to be taught? If so, should they be taught at the same time? Would that save time or create confusion?

Specific locations in the text – Sometimes the glossary will tell you where the term is discussed in the text. Take a glance at the section of the text and see if the term will be naturally taught in the course of the lesson.

A trip through the glossary takes some time, but it’s time well spent.

You’re heard of “a stitch in time saves nine”? Yeah, it was talking about this step.

Look at Data from Previous Students

We can look at all the lists in the world of words that “should” be taught in certain grades, but you’re not a teacher for nothing.

You know your students. You know yourself. You know your curriculum.

(If you don’t now, you will in a few years! Stay tuned!)

Trust yourself.

This doesn’t have to be formal. Simply think to yourself:

- What words cause my students issues historically?

- How often does this term created confusion?

- How often does this term/word show up on tests in important ways?

- Does my gut tell me that my students need good teaching of this word?

These questions will guide you as well as any other metric.

Your teacher intuition is a powerful thing.

Now that you’re focused on vocabulary instruction, you’ll be looking for these words. You’ll have your eye out, and over time, you’ll gather a list of words that you know are the words that your students need most.

Look in the Reading

If you’re an early elementary or ELA teacher, you’ll find most of your words by looking at daily text.

Let’s say you’re a fourth grade teacher reading the book The Secret Garden.

You glance through the chapter before you do the reading. You look for words you think your students might not have sufficient familiarity with.

Here’s a passage from Chapter 13:

But you never know what the weather will do in Yorkshire, particularly in the springtime. She was awakened in the night by the sound of rain beating with heavy drops against her window. It was pouring down in torrents and the wind was “wuthering” round the corners and in the chimneys of the huge old house. Mary sat up in bed and felt miserable and angry.

“The rain is as contrary as I ever was,” she said. “It came because it knew I did not want it.”…

She threw herself back on her pillow and buried her face. She did not cry, but she lay and hated the sound of the heavily beating rain, she hated the wind and its “wuthering.” She could not go to sleep again. The mournful sound kept her awake because she felt mournful herself. If she had felt happy it would probably have lulled her to sleep. How it “wuthered” and how the big raindrops poured down and beat against the pane!

A few words stand out, and you highlight them. You run them through the three questions and decide that they are all worth teaching.

You might hesitate over wuthered, but it has come up in earlier chapters, so you let it go.

Rinse, repeat.

This is the process for Tier Two words.

To do this well, it does require that you prepare lessons in advance. It doesn’t work if you do it at the last minute because you have to prepare how to teach them.

One last point here: the technique is not to do an internet search for “Secret Garden vocabulary.”

It’s fine to start there, especially if you’re a first- or second-year teacher.

Over time, you’ll get a feel for the words your students need most.

? How do you know if the word is appropriate for the learning level of the student?

You may have words that you’re concerned about teaching because you think they may be “too hard” or “too easy” for your students.

Is there such a thing as Goldilocks words? Words that are just right?

While it can seem like a party trick when a young child uses a word bigger than themselves, even young students are capable of learning big words and using them appropriately.

Sometimes, kids like learning big words. They’re like a toy made for a big kid.

High ability students often have vocabulary superpowers and learning “big” words is a great way to challenge them.

Sometimes, students haven’t learned “easy” words you’d think they should have learned in an early grade but somehow missed.

Don’t get hung up on when students should or should not acquire words for their vocabulary toolbox.

Rather, consider the three questions like you would for any word. If the word passes the test, it’s not syllables that make it a word worth teaching.

Beck, McKeown, & Kucan say that two things make a word inappropriate for teaching:3

- If you can’t explain it to students in words they know

- If the word isn’t useful or interesting or won’t be encountered in their daily lives

I feel like the second question is answered in the three staple questions with the exception of seeing it in their everyday lives.

So, if you can explain it to them in a way they would understand, and the word meets the three questions, don’t be dissuaded by a word that seems too “hard.”

Similarly, just because it seems like they should have learned a word the year before, or even years and years earlier (!), that’s not what’s important.

What’s important is what they know now and what they need to know.

Don’t die on the hill of “they should already know this.”

? How Many Words Should You Have at the End of the Process?

Tier One words: None. These are words we don’t need to teach intentionally.

Tier Two words: If you are an early elementary teacher or an ELA teacher, you may have as many as 400 of these words.

For Tier Two words, you will not necessarily identify them at the beginning of the year. You will find these at the beginning of units or lessons.

Tier Three words: I try to limit these to 80 words a year or so, although that may not be possible with term-heavy content. Typically, if you have content like that, you will have few Tier Two words you need to teach.

?Wrapping Up:

Our key takeaways from this article are:

- There are three tiers of vocabulary words, and teachers focus on Tiers Two and Three

- When considering whether to teach a specific word, we ask three questions:

- Is this word one students will be able to use frequently enough to make it worth it?

- Is this word one they will need to be able to demonstrate content mastery?

- Is this word students may need in order to express themselves precisely?

(And you can grab the simple index-card sized printable of these questions.)

- We find the words to teach in our standards, glossaries, data, and reading.

- Word appropriateness isn’t as complicated as it seems.

- We may have as many as 400 words to teach, but it’s not as intimidating as it sounds.

Great vocabulary instruction will be made less great if we don’t make good decisions about word choice.

Let’s use these tools and techniques to choose the words worth teaching to best support our students and save ourselves instructional time.

? You May Also Like:

Wow! You made it through this super comprehensive article! Congrats! If you’re interested in more about vocabulary instruction, I’ve got some ideas for you.

If you’re ready for some actitivities and games, I’ve got you covered:

- Tonight Show Teaching: Teaching Vocabulary with Word Sneak

- Harry Potter Sorting Hat Vocabulary Strategy

- Vocabulary Categories Relay Game

If you want more theory (go, you!), you can find some of that here:

- How to Teach Denotation and Connotation

- 7 Reasons Etymology is Important for Teachers

- How to Use Semantic Maps to Teach Vocabulary

? Works Cited:

- Beck, McKeown, & Omanson (1987). The effects and uses of diverse vocabulary instructional techniques. In McKeown & Curtis (Eds.), The nature of vocabulary acquisition (p. 147–163). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

- Cocking & Chipman (1998). Math achievement of language minorities. In Cocking & Mestre (Eds.), Linguistics and cultural influences on learning mathematics (p. 29). Routledge.

- Beck, McKeown, & Kucan (2013). Bringing words to life. Guildford.

- Nagy, William E., and Richard C. Anderson. “How Many Words Are There in Printed School English?” Reading Research Quarterly, vol. 19, no. 3, 1984, p. 304.