When you get a great critical thinking exercise and pair it with a great vocabulary activity…well, let’s change their Facebook status to “in a relationship with…”

Semantic Maps are just such a pair. Let me persuade you!

Semantic Maps are a tool we use to help students to identify, understand, and recall the meaning of words they read in the text.

They’re research-based, they lend themselves to use with graphic organizers, they support struggling readers, and they are easy to use.

I’ve found that lots of teachers think they’re a great idea, but aren’t sure of exactly how to implement them in a real classroom.

? What is a Semantic Map?

- Semantic Maps are a visual strategy for teaching vocabulary.

- “Semantic” just means “related to meaning in language”, so a semantic map is essentially a “map” that connects related words.

- With Semantic Maps, students create “maps” or webs of words.

- Words are sorted into categories based on what they are, what they do, or other categories.

- Semantic Maps can be very simple, using just words grouped together, or they can be more complex, using graphic organizers or other visual structure.

- Often, the words are generated as a list and then coverted in a more visual format.

- Semantic Maps can be created on paper or digitally.

- Semantic Maps can be created individually, in small groups, or as a whole class activity.

- Semantic Maps are dynamic. Students can add to their maps as they learn more information and gather more words.

Do Semantic Maps sound like something that could be useful to your students? I’d love to tell you more about exactly how they work in class.

? How are Semantic Maps different from graphic organizers?

First, let’s look at what they’re not.

While Semantic Maps may use a graphic organizer to arrange the words, Semantic Maps go beyond just a graphic organizer.

The don’t ask students to recreate already mastered/learned information.

They ask students to think, “What do I know related to this? What does this make me think of?”

Their strength is that they build on students’ current schema or understanding, allowing those neural pathways to fire up.

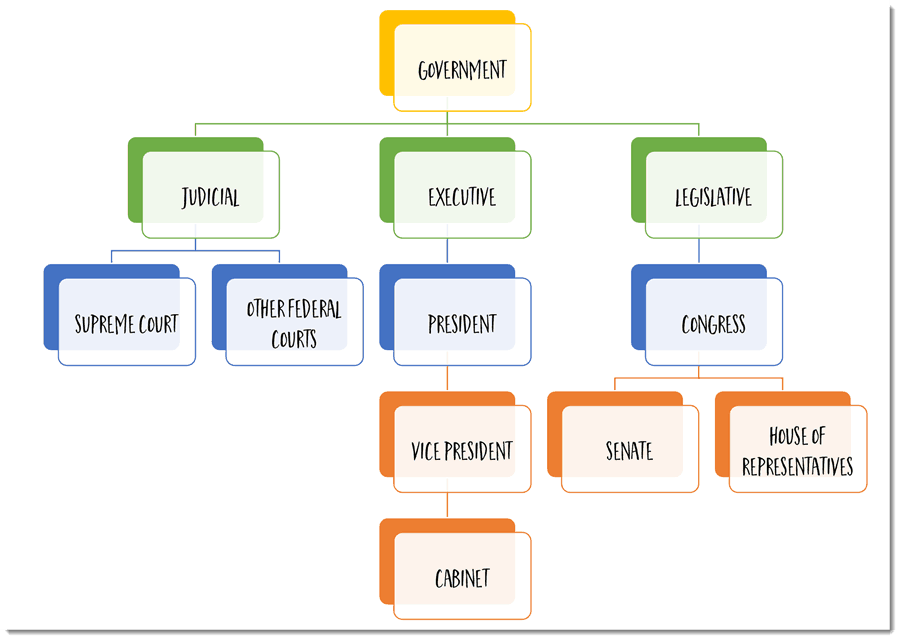

Here’s an example of a graphic organizer I created using Smart Art in PowerPoint. This has one “right” answer, doesn’t it? If a student put anything else under “legislative”, we’d be worried, wouldn’t we?

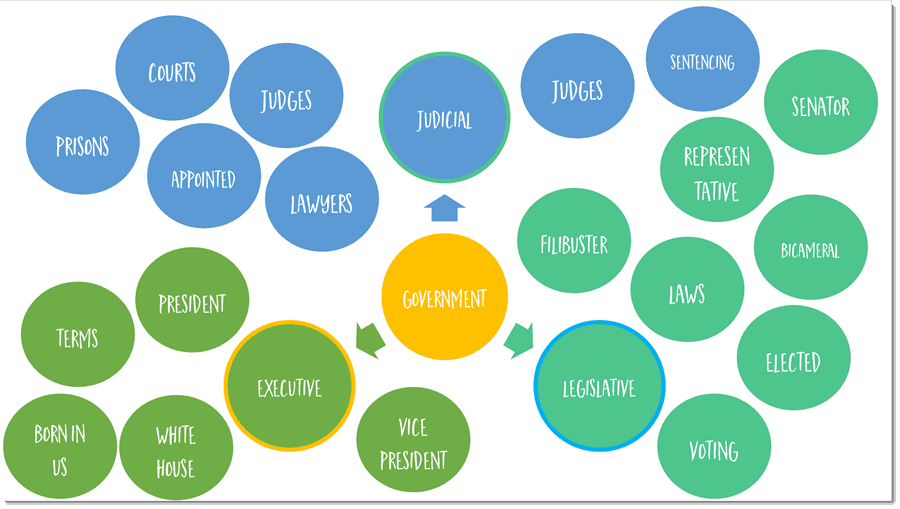

Here’s a Semantic Map over the same topic. In this case, I just gave the student the word “Government” in the center, along with the three branches of government. The student then created the Semantic Map, generating lots of words related to those three areas. This was also created using Smart Art and shapes in PowerPoint:

Do you see the difference? We’re still looking at branches of government, but we’re going to get different results from different students.

It requires less rote recall and more thinking.

I’ll be coming back to graphic organizers later.

? How do I teach students to use a Semantic Map?

When introducing Semantic Maps to students, I find it’s best to guide them in two processes: generating words and then grouping or categorizing those words.

For example, let’s say we’ve just had a lesson on the structure of the cell. For a review, I could write the term “cell structure” on the board (or screen) and ask students to think of all the words they can think of related to cell structure.

Tell them to think of words that:

- define what we’re talking about

- describe what we’re talking about

- tell the purpose of what we’re talking about

- give information about what we’re talking about

I could do this as a whole class activity, have students work in pairs or groups, or have students work individually.

Once we had a list of words and terms, I would ask them to sort those words into groups. I can either give them categories, or I can have them come up with categories on their own.

If students are coming up with their own categories, tell students that to this, they need to think about ways in which the words are alike and ways which they are different.

Once they’ve grouped their words, they come up with a word or term that describes the group.

If I’m giving students the categories, I will simply tell them what they are and have students sort their words into the category in which they think they fit. That’s what I did in the government example above.

For my cell structure example, I’d give students the categories Nucleus, Cytoplasm, and Cell Membrane.

You can use Semantic Maps as a simple daily activity that takes only a few minutes, or you can have students work with them to create a visually pleasing representation.

? Semantic Maps Step-by-Step

There’s no one right way to use Semantic Maps (you’ve already seen a couple of ideas here), but I did want to share a sample idea that is a great way to get started if you’re unfamiliar with the strategy.

- Choose a word from the text you’re using. This could be a textbook, a story, or any other part of your curriculum.

- Write that word on the board or using a digital tool. Just make sure everyone can see it.

- Have students look at the text that’s near that word to see if there are any words that are connected to this target word.

- You may wish to have students look up the word in a dictionary or thesaurus (that would add to the standards addressed!).

- Brainstorm words the class can come up with that are related or connected to this word in some way. Remember, these should not only include examples of the word (“cat” is an example of an animal, for example), but also what the things can do. For instance, “can fly” or “can run”.

- Once you have a robust list of words, then you do the categorization. Remember, you can give categories or you can have students generate categories.

- Now, transform these into a map. This can be a circle with spokes coming off of it or a more formal graphic organizer.

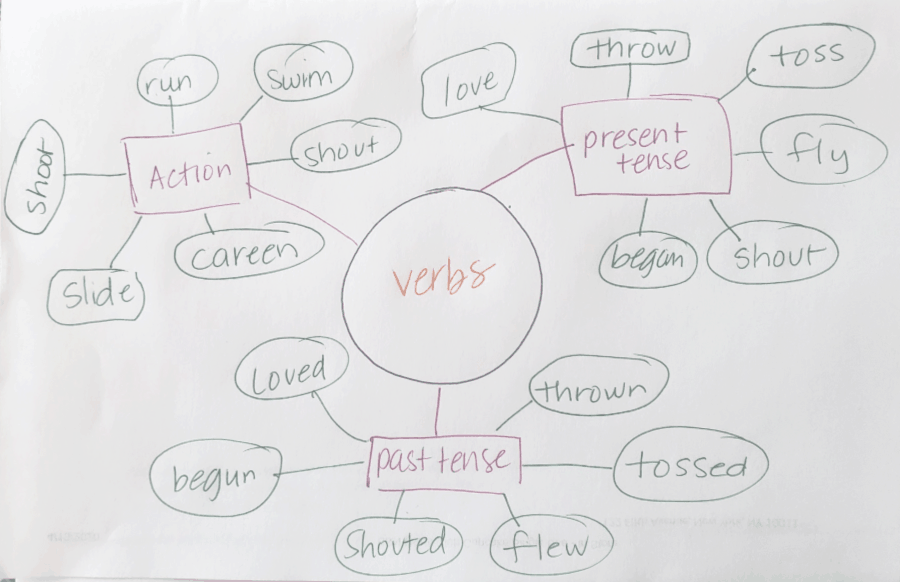

Here’s an example of a simple one generated after a discussion of verbs.

? How can I use Semantic Maps with technology?

You’ve seen above how you can use PowerPoint to create Semantic Maps. There are other tech tools that work, as well.

This table lists some possible tech tools, with the pros and cons of each.

| TOOL | COST | PROS | CONS |

|---|---|---|---|

| PowerPoint/ Keynote | Free | Students probably familiar with it; very flexible; easy to convert to other formats (images or PDFs); SmartArt has built-in graphic organizers | Harder to integrate with other platforms (uploading, etc.); difficult to collaborate; takes more time than some other tools. |

| Google Slides | Free | Same as PowerPoint except Smart Art | Not as powerful as PowerPoint, so fewer possibilities. |

| Google Draw | Free | Very similar to Google Slides, except a little more flexible | Students are usually less familiar with this than other Google tools. |

| Google Jamboard | Free | Built for collaboration; easy to use; easy to share; easy to add images; no need to own software | Students may be less familiar with this than other Google tools. |

| Bubbl.us | Freemium (free & paid versions | Built for collaboration; browser-based, so no software to download or install; low-distraction interface; easy to share; easy to present with | The free version is very limited, which gets frustrating very quickly. |

| Mindmup.com | Freemium (free & paid versions) | Easily converts to PDF, PowerPoint, or outlines; easily save to Google Drive; add images or even documents; easy to share | Students and teachers are usually unfamiliar with it, so there will be a learning curve. |

? What are the benefits of using a Semantic Map?

Semantic Maps are particularly useful for students who are struggling or who are English Learners, but they work really well with everyone.

First, we have the creativity side. One of the Torrance Traits of Creativity is Fluency – coming up with lots of ideas.

That’s the first part of what we do with a Semantic Map.

Next, we have the added strength of categorizing. Sorting and categorizing are powerful tools. We see it in little children sorting blocks, but the power of dividing things into categories or groups isn’t something that ends in Kindergarten.

We can have students come up with their own categories, or we can give them the categories we want them to use (as I demonstrated above).

If we really want to up the ante, we can have them create new categories and recategorize all of the words. That’s super fun!

Another benefit of Semantic Maps is that they are a no-prep activity. Nothing to print out. Nothing to copy. Just minds and something on which to write. It just doesn’t get easier than this.

? How do Semantic Maps work with graphic organizers?

While you don’t need to use a formal graphic organizer to create a Semantic Map, they go very well together.

Almost any graphic organizer can be used as a Semantic Map.

If you use Thinking Maps®, then a Bubble Map® or a Double Bubble Map® would be my first choice.

The key is to pick a graphic organizer that works for the students, so it’s less about what it looks like and how effective it is in helping them create a visual represenation of their thinking.

You’ve got a few options:

- Give students a particular graphic organizer that you want them to use

- Give students a few graphic organizers they can pick from to use

- Have students generate their own graphic organizer

- Let students search for a graphic organizer

The most important thing is to not let the organizer become more important than the thinking!

? How do Semantic Maps align with standards & research?

Semantic Maps have been studied in research, and those studies have shown some strong benefits.

Semantic Maps are a part of the group of “[i]nstructional activities that allow for a visual display of words and promote students’ comparing and contrasting of new words to known words [that] can be a beneficial means for increasing their vocabulary knowledge” (Rupley, Logan, & Nichols, 1998).

As we practiced above, Semantic Maps not only identify important ideas, but they also show the relationships among those words and ideas (Kholi, & Sharifafar, 2013).

That’s where research shows their power lies.

As far as standards, clearly they address some of the CCSS ELA standards, such as:

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.L.3 Apply knowledge of language to understand how language functions in different contexts, to make effective choices for meaning or style, and to comprehend more fully when reading or listening.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.L.4 Determine or clarify the meaning of unknown and multiple-meaning words and phrases by using context clues, analyzing meaningful word parts, and consulting general and specialized reference materials, as appropriate.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.L.5 Demonstrate understanding of figurative language, word relationships, and nuances in word meanings.

But you also see them apply in math standards such as:

CCSS.MATH.CONTENT.6.EE.A.2.B

Identify parts of an expression using mathematical terms (sum, term, product, factor, quotient, coefficient); view one or more parts of an expression as a single entity.

If you’re using Next Gen Science Standards, Semantic Maps are a strategy for Crosscutting Concepts, as students begin to recognize the patterns.

These are just examples. Whatever standards system you’re working with, Semantic Maps fit beautifully.

? How do I use Semantic Maps in Writing?

Semantic Maps can be used to organize thoughts before writing, creating a structure students can follow. They are a perfect pre-writing strategy.

When students group their ideas, they can easily see where there is unbalance.

They can then add in more details where they are lacking or eliminate some where they have too many.

? Wrapping Up

Semantic Maps are a vocabulary strategy that belong in every teacher’s toolbox. I hope that after reading this you feel confident in giving them a try.

There’s no “wrong” way to do them and the rewards are terrific, so go ahead and see how they work with your students.

Like anything else, it may take a few tries until you (and your students) feel comfortable.

Pretty soon, the strategy will be second nature to you! ?

? You May Also Like:

- Playing with Concept Cubes to Teach Vocabulary

- Teaching Vocabulary with Depth and Complexity Frames

- Harry Potter Sorting Hat Vocabulary Strategy

? Would you like to come to the Luau?

Join in the luau! You’ll be in the know on all things vocabulary and get any new freebies that come out, even if you miss the article.

Sign up and get a free two-page list of vocabulary question stems!