Usually when we use the term “vocabulary,” we mean understanding a word’s definition so that you can use it and bring it into your own personal lexicon.

You can’t study vocabulary without looking at the definitions of words. But it’s not that simple. Words convey much more than their dictionary definitions suggest.

As a language arts teacher, one of the things that I have found rewarding and challenging is helping students understand the difference between denotation and connotation.

If students don’t know the connotations of a word, they can make grave errors in reading, speech, and writing.

? What are denotation and connotation?

Denotation is the dictionary definition of the word. It is what the word technically means.

Connotation is the feeling, emotion, cultural implication, or overtone associated with the word. Connotations may not appear in a dictionary, yet they are equally important to understanding and using the word.

As words change and shift in meaning over time, connotations will move much faster than denotations. The dictionary lags behind contemporary social norms of how we view language and what words are acceptable to be used and what words are not.

Different cultures will find different words offensive, not necessarily because of the denotation, but because of the connotation. Connotation is often culturally and socially dependent.

? Introducing the idea of denotation and connotation to students

To introduce denotation and connotation to students, I use one of two methods.

? Words and Genes

I use the Words and Genes method with secondary students.

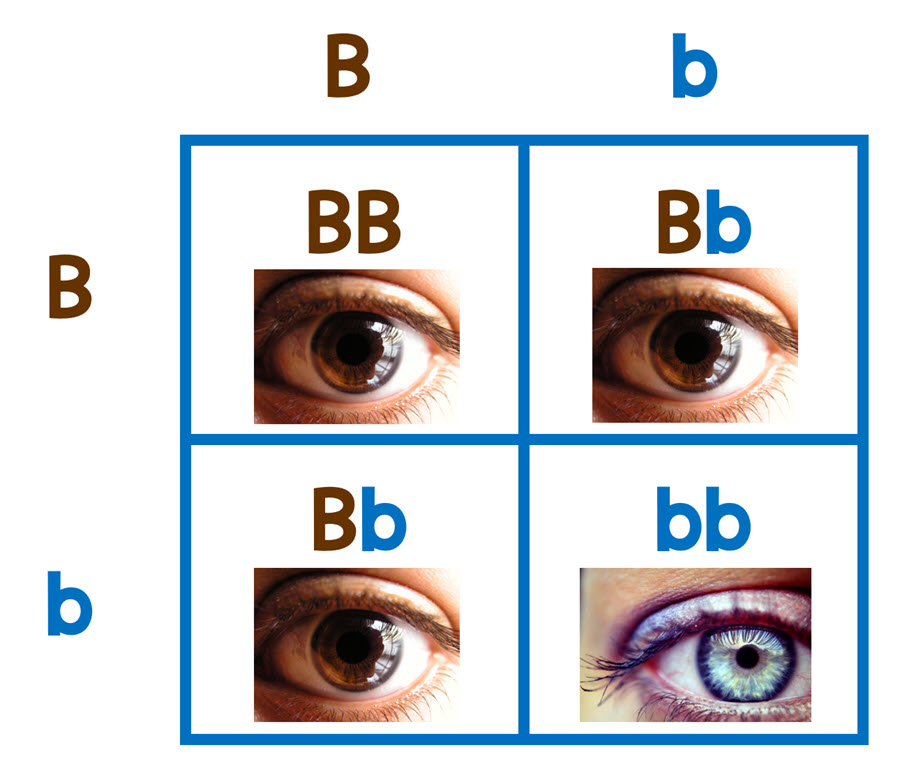

In genetics, your genotype is what your genes actually say. Your phenotype is what you look like. For example, you can have brown eyes, but still carry the gene for blue eyes. Your genotype may be mixed, but your appearance is not.

I show this Punnett Square I made of two brown-eyed parents who both carry the gene for blue eyes. Because blue eyes are recessive, if you carry the gene for brown eyes, you have brown eyes. That’s true, even if you also carry the gene for blue eyes.

In this example, I point out to students that everyone gets one gene from their mother and one from their father. If these two people had children, the odds are that 1 in 4 of their children would carry two brown eyed genes, 1 in 4 would carry two blue eyed genes, and 2 in 4 would carry one brown and one blue, just like the parents.

Three of the children would have brown eyes, yet that wouldn’t tell the full story. What your genes say isn’t always what your genes express. You can’t tell by looking at a brown-eyed person what their genes say.

Words are like this, too. They have a genotype – what we call the denotation. It’s what the dictionary says the word means.

And they also have a phenotype, what we call the connotation. It’s what the word looks like and feels like when its used.

For some reason, this explanation makes total sense to kids. They get it right away that something could actually be one thing, but look like something else.

? Explaining to elementary students

With elementary students, I jump right in with a sorting game to explain denotation and connotation.

I give them pairs of words and tell them to yell out the one that has a more positive meaning than the other. Yep, I tell them to yell. There’s something about the energy that creates that’s fun. You can have them whisper. It’s up to you.

Here are some examples:

- thin/skinny

- cook/chef

- house/home

- refreshing/chilly

- weed/plant

- exciting/scary

- insect/pest

I explain that even though the words may mean the same thing if you look them up in the dictionary, it would feel very different if someone called you “exciting” or “scary.”

For both groups, next I share a list of words, and we put them in order from positive to negative in meaning.

Here are some examples:

- smart, clever, bright, brilliant, intelligent, sharp, streetwise, brainy, wise

- difficult, challenging, tough, demanding

- painful, distasteful, agonizing, uncomfortable, terrible

- tasty, yummy, delicious

I wrap up by having students work in pairs or groups of three to sort words into categories of “positive words,” “negative words,” and “neutral words.”

I’ll give them a list of words to sort into these categories, such as:

- friendly

- lazy

- timid

- shy

- quiet

- outgoing

- beautiful

- terrible

- difficult

- person

- angry

- emotional

After they’ve sorted, we discuss what we did. It’s always surprising how many differences the students come up with. That’s the point we’re making – that words can take on different meanings in different circumstances.

I end with sharing the idea that we will be looking at the dictionary definitions of words, called the denotation, and the feelings and meanings associated with the words, called the connotation.

? Denotation and connotation activities

Because connotation is about feeling and perception, it benefits from using activities to work with it, rather than just listing, “This is the denotation. This is the connotation.” That’s no fun.

Here are a few activities you can use with students to help them understand the concept of denotation and connotation.

? Match Me

To use the Match Me activity, gather words that have a denotation completely unrelated to their connotation.

Make a memory matching game by writing or typing the denotation on one card and a connotation on another card. Students take turns turning over cards to find the match. They get to keep the match if the match is correct *and* they can come up with a word that means both things.

The connotations may be either positive or negative.

It’s important that the teacher keep a list of the matches because they are not obvious!

Some examples include:

- Word: Unique

Denotation: the only one of its kind

Connotation: peculiar or weird

- Word: Cool

Denotation: of or at a fairly low temperature

Connotation: hip

- Word: Delicate

Denotation: easily broken or fragile

Connotation: weak

- Word: snake

Denotation: a long, limbless reptile

Connotation: a deceitful person

You can use this activity with any words to teach the idea of denotation v. connotation, or you can come up with connotations for the vocabulary words you’re working on. Not every word has a connotation that differs from its denotation, so you may wish to collect some over several vocabulary lists and combine them into a single exercise.

? Old School Words

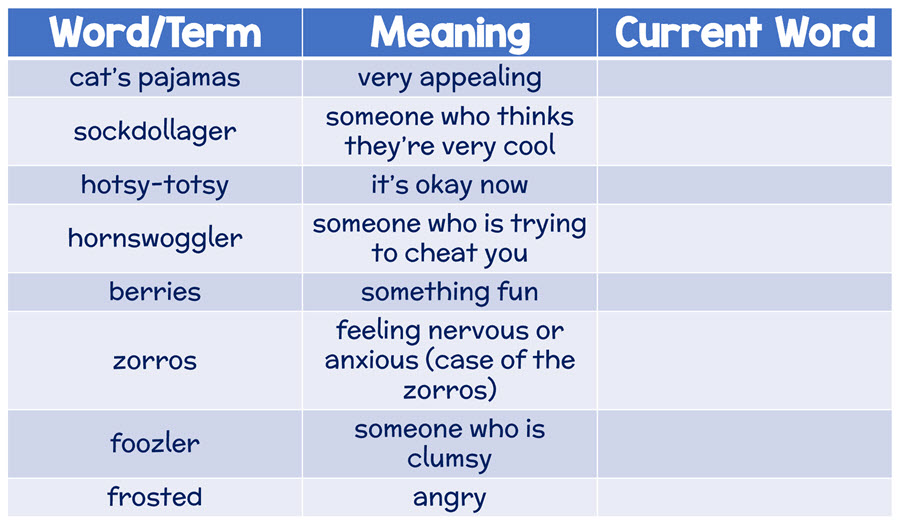

In this activity, I share a list of words that used to mean something different from what it means now. I usually choose slang expressions because they’re the funniest.

I draw three columns on the board or screen. I put the word in one column, the meaning in another column, and students come up with a current term that means the same thing in the third column.

This one is best done as a class because the students usually love it. Heads up: there will be lots of laughing!

? Depth& Complexity Ethics Game

For a little bit more serious activity, I use the Depth and Complexity Ethics ⚖️ prompt to evaluate words.

I share a word, and we discuss:

- Has this word always had the connotation it has now?

- What are the possible positive and negative connotations of the word?

- What kind of misunderstanding could arise if someone uses the word with the denotation in mind and someone else hears that word with the connotation in mind?

- Who would most benefit from using the denotation or the connotation?

- If a word changes in connotation, is everyone required to accept the new connotation?

? Sentence Remix

For this activity, I give students sentences (or have them create them and trade with a partner) and have them identify a word in the sentence that has a positive or negative connotation. They then replace that word with a word that has the opposite connotation.

Here are some examples:

- She lives in the heartland of America. (Could be changed to “She lives in a flyover state.”)

- My parents are so nosy about what I’m doing. (Could be changed to “My parents are so interested in what I’m doing.”)

- She’s super frugal because she’s saving for college. (Could be changed to “She’s super stingy because she’s saving for college.”)

- They have a lot of confidence in their abilities. (Could be changed to “They have a lot of arrogance about their abilities.”)

? In the News

For this activity, share paragraph-length newspaper clips with students and have them evaluate the paragraphs looking for loaded words.

To make this activity most effective, choose paragraphs from different sources about the same event or story.

In order to offer sources that are centrist, as opposed to those with a clear political leaning, I find the paragraphs at:

For example, here’s a paragraph from the Conversation about the polio vaccine:

In 1955, after a field trial involving 1.8 million Americans, the world’s first successful polio vaccine was declared “safe, effective, and potent.”

It was arguably the most significant biomedical advance of the past century. Despite the polio vaccine’s long-term success, manufacturers, government leaders and the nonprofit that funded the vaccine’s development made several missteps.

When students examine a paragraph like this, I want them to see that even words like “successful” can be loaded.

I want them to look for clue words that indicate a loaded word is coming up. In this example, “arguably” is a clue word that leads us to the loaded “most significant” term.

In addition to identifying loaded words, they can also rewrite the paragraphs to make them more or less neutral.

Social Justice

Connotation is a powerful tool. Words can be used as weapons, and the meanings of words are often loaded.

If you teach older students, you may wish to consider exploring loaded words with them. This must be approached delicately, as even sharing them in order to show that they have been used in hurtful ways can in itself be hurtful.

If it is appropriate for your students, you can explore words related to race and gender and how different groups view different words.

We can explore such topics as:

- Who gets to decide what a group of people are called?

- How do we get everyone on board to new terms?

- What if I’m in a group of people that some want called one thing, but I prefer a different term?

- What responsibility do we have to use words that are acceptable to the person we’re talking to or talking about?

To begin with this very delicate topic, I may have students read an article about how we have changed in the way we name races over time. (Here’s an example of one such article.)

Again, this is delicate. Only engage in this kind of discussion if you feel that you have created a safe classroom environment, if it is connected to your standards, if you have the positional authority to keep the conversation respectful, and if you can be neutral yourself.

? Differentiation

Often, our high-ability students have advanced language expression and may have already mastered vocabulary we are explicitly teaching our on-level students.

Denotation and connotation can make an excellent research project for those students. High-ability students can explore connotations of words, and they can even do some research on it.

They can select a list of words and then interview people to ask if the words have a positive, negative, or neutral connotation to them. Students can share their findings in charts, if you’re wanting them to work on that, or in written form.

? Wrapping Up:

One of the quickest, yet most effective critical thinking skills when introducing new vocabulary is to consider the difference between denotation and connotation.

Once you’ve taken a little bit of time to make sure students know what you mean by these terms, you will have a go-to strategy to deepen the thinking surrounding vocabulary words.

? You May Also Like:

- How to Use a Linear Array to Teach Vocabulary

- 7 Reasons Etymology is Important for Teachers

- Teaching Vocabulary with Depth & Complexity Frames

? Want to be an insider?

If you’d like to be a Vocabulary Luau insider, join in here. You’ll get a list of vocabulary question stems when you join in, and you’ll always be in-the-know about great articles, games, and freebies to help you teach vocabulary (with a hint of hula?, of course!).