The Frayer model is one of the few tools for teachers that’s been in classrooms longer than I have. When I first started teaching, I was using it, and it’s still going strong in classrooms around the world.

Let’s find out why it’s enjoyed such long-lasting popularity.

? What is the Frayer Model?

The Frayer model is a categorizing activity that helps students deepen their understanding of concepts.

It also helps teachers evaluate the level of student understanding of concepts.

When done well, it guides students to the synthesize level of Bloom’s.

If you’re a teacher, you’ve probably heard of the Frayer Model.

Like many older teaching strategies, it’s gone through the educational version of the telephone game where we’ve heard about what it is, but we’ve strayed from the origins.

A Frayer Model evaluates concepts through four lenses:

- An operational definition

- Characteristics

- Examples

- Non-examples

A graphic organizer is often used in conjunction with the Frayer model, but the theory doesn’t require it.

The Frayer Model is usually used to teach vocabulary and deepen students’ understanding of concepts.

Because the Frayer Model is a mainstay of instruction (and has been for fifty years) it’s worth exploring in more depth.

? The Four Parts of the Frayer Model

Typically, the Frayer Model has the four parts listed above (definition, characteristics, examples, non-examples).

Definition:

Because this is in the upper-left hand of the common graphic organizer structure used with the Frayer Model, people think it’s the part students should complete first.

In actuality, it’s best if this is done last. The idea is that as the students work with the concept, they’ll be better positioned to construct a definition.

The definition should summarize what the student understands about the concept as represented by the other three categories.

Characteristics:

In this section of the Frayer Model, students identify the common characteristics of the concept.

This is the section students should begin with.

It’s here that students answer the questions:

- What is this concept?

- What does it have to have to be this thing?

- What distinguishes it from other things?

If you use the Depth and Complexity framework, this is Details.

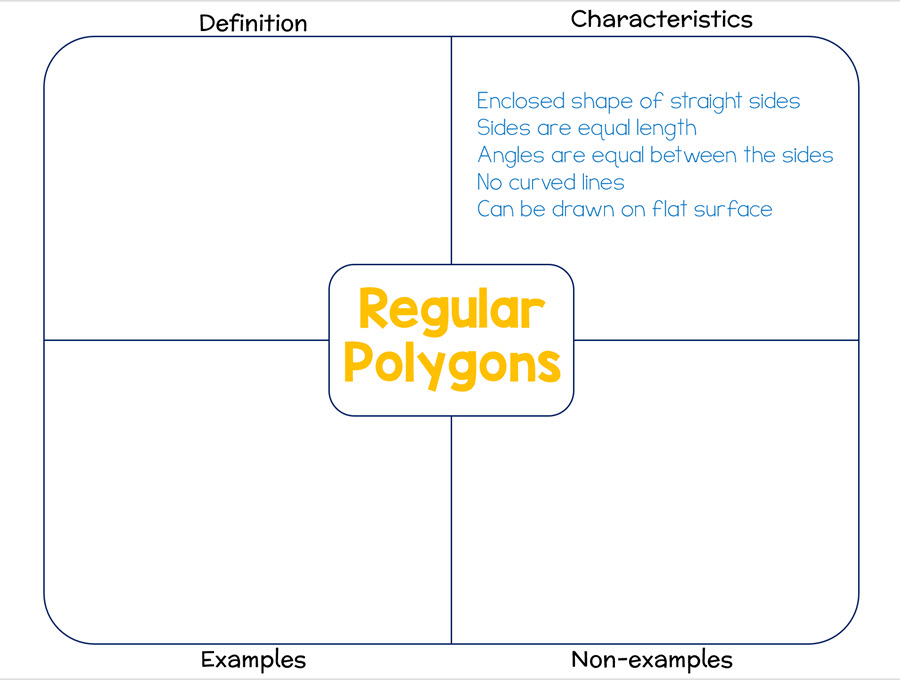

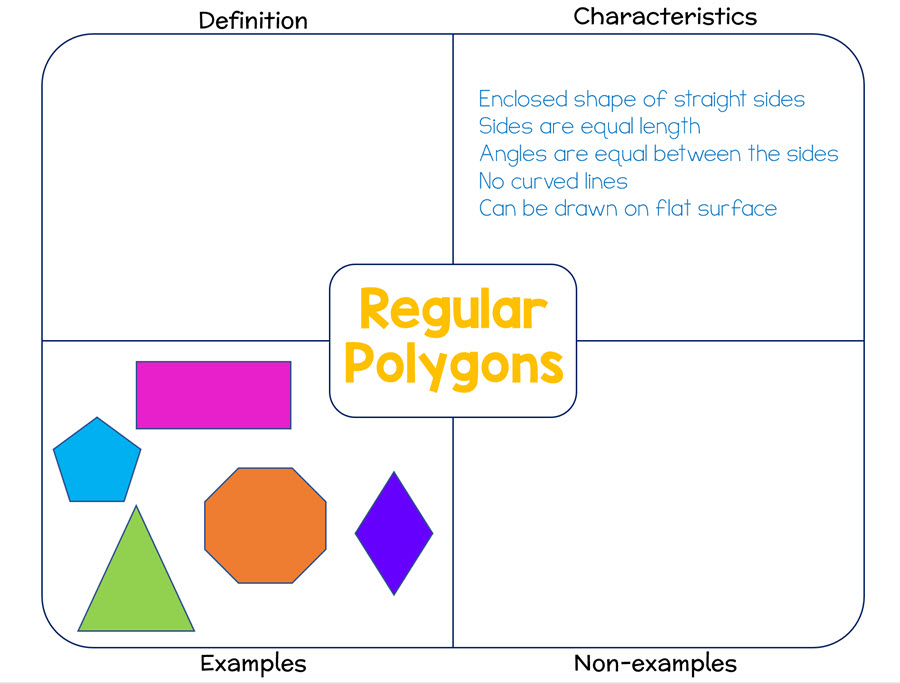

Here’s an example for the concept regular polygon.

Examples:

In this section of the Frayer Model, students include examples of the concept.

While it’s useful to generate several examples, what’s most important is that students select examples that truly exemplify the concept.

The idea is that someone wouldn’t look at the list of examples and think, “Well…”

We want solid examples.

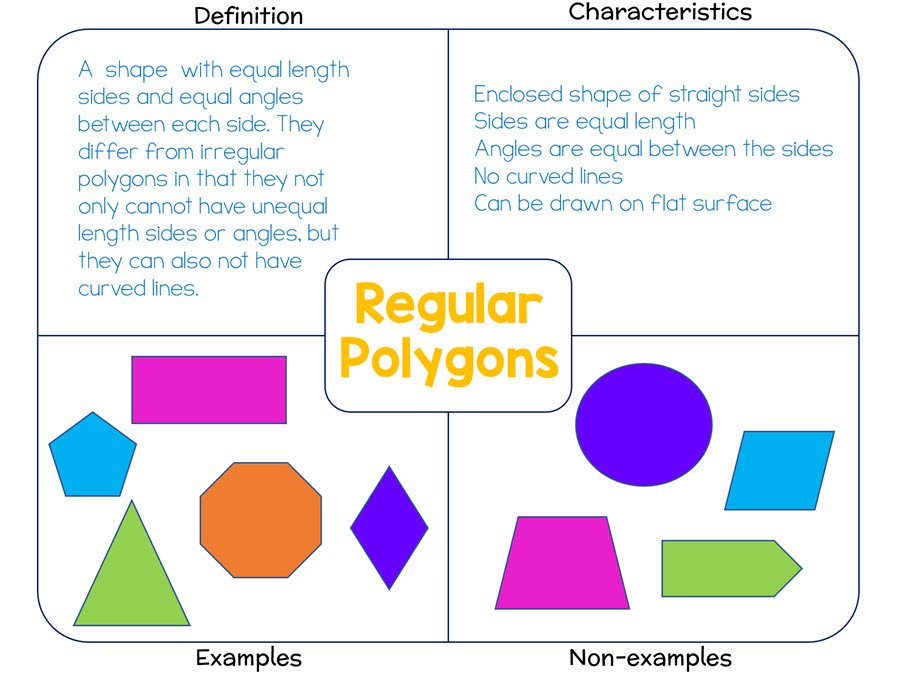

Here’s what that looks like with our regular polygon concept:

Because this is a concept that lends itself to visual examples, I’m going to expect students to draw (or insert) shapes, rather than list them.

If I had a concept like simile that lends itself to word representation, I would expect students to find or create examples like:

- He is as strong as an ox.

- She is as boring as a restaurant with no wi-fi.

- They resemble a tornado just before it hits you.

Non-Examples:

In the non-examples analysis, students should include things that are definitely not associated with the concept.

Just as we wanted strong and clear examples, we want strong and clear non-examples.

If you are exploring the concept of fruit, you wouldn’t want students to include tomato here because many people classify tomatoes as fruits, not vegetables.

Here’s what our non-example regular polygons looked like:

Now that students have explored the characteristics, examples, and non-examples, they’re ready to craft a definition:

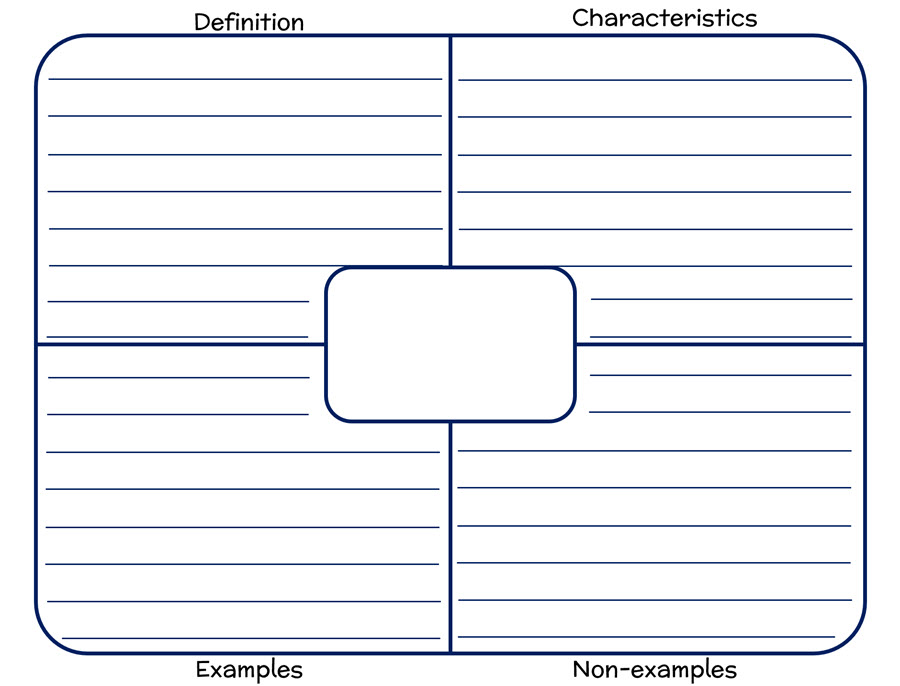

? Frayer Model Template

While the common graphic organizer we associate with the Frayer Model is not strictly necessary, it is helpful (as are so many graphic organizers).

I make mine in PowerPoint using SmartArt.

I made a video to show you how to do that in five seconds. Yep.

<div align="center"><iframe width="560" height="315" src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/n3TUZl8RYqs" frameborder="0" allow="accelerometer; autoplay; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture" allowfullscreen></iframe></div>Want to have me do it for you?

You can download the one I used in the example. It includes both the blank version and a version with lines in case you want to help students write straight!

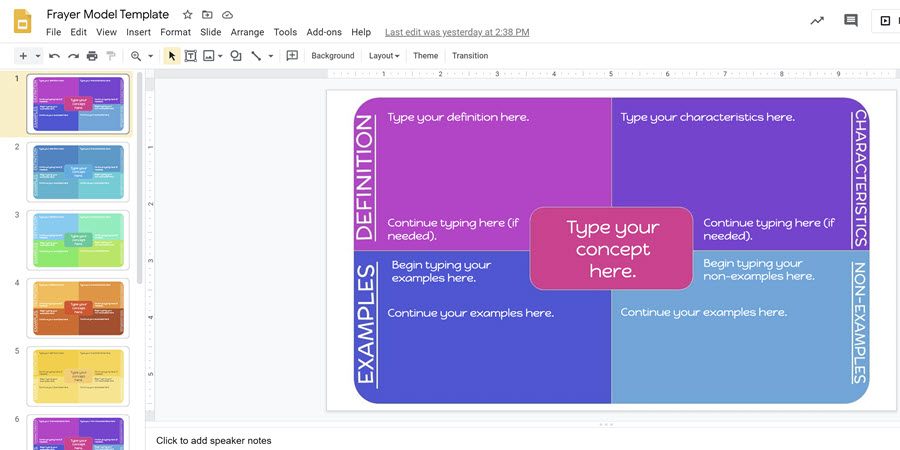

I’ve made a digital version for use with Google Classroom™ that looks like this:

Join in on the Vocabulary Luau party to copy it to your own Google Drive.

? Using Alternative Categories in a Frayer Model:

While the common model is the one described so far, you will also see a version with slightly different categories.

This alternate version uses these categories:

- essential characteristics

- non-essential characteristics

- examples

- non-examples

The Google Slide template has both of these versions.

Another alternative is to use these categories:

- definition

- examples

- synonyms

- antonyms (use same/opposite for younger students)

All of these versions have their uses. The one you choose will depend upon the concept being explored and the ability of your students to evaluate the concept with depth.

? When should you use a Frayer Model?

The Frayer Model is particularly useful in four scenarios.

First, teachers can have students create a Frayer Model before reading a text to determine the mastery of the academic vocabulary in the text.

It will be difficult to teach the importance of the American Revolution if the students don’t understand the concepts of democracy, freedom, or colonialism.

Next, teachers can have students construct a Frayer Model after instruction is complete as a review activity.

A third opportunity is after reading/learning as a check for understanding or exit ticket.

Doug Buehl also encourages the use of the Frayer Model to help students determine the importance of the concept.

In my experience, this is best done by comparing several concepts at once, rather than a single concept in isolation.

? Why is the Frayer Model Effective?

For some reason, we’ve gone backwards in a lot of our pedagogy, and our students deeply benefit from the ideas of concept attainment first put forward by educational psychologist Jerome Bruner.

Lots of other researchers began exploring this idea, and they developed many strategies and models that help teachers get at the heart of learning.

Whenever you hear someone complain about “rote learning,” they’re talking about how far we’ve come from these ideas.

So, Frayer is a return to those models of learning acquisition.

It has practical benefits as well. Here were just some I thought of:

- Students actually work with terms, rather than memorizing definitions

- Frayer is a stronger cognitive exercise than most games (although I love vocabulary games)

- It works across multiple grade levels and content areas

- Frayer invokes prior knowledge to build connection to new concepts

- When the graphic organizer is used, it creates a visual representation

- It allows for comparison of attributes and examples among concepts

- Frayer helps students identify and understand unfamiliar vocabulary

- It can be used in individual, small group, or whole class activities

- Allows teachers to assess student understanding as well as teach the concept

- It can be used to give students the opportunity to clarify and share their thinking

- It doesn’t take long to implement and is easy to use.

- Students generate accurate and comprehensive definitions

? Who invented the Frayer Model?

The Frayer model was developed by the Wisconsin Research and Development Center for Cognitive Learning at the University of Wisconsin in 1969 by Dorothy Frayer, Herbert Klausmeier, and Wayne Frederick.

They had been working on the idea of concept attainment, and the model arose from their identification of the disconnect between labeling concepts, defining those concepts, understanding the relationships among concepts, and how you apply concepts.

The model is designed to help measure different levels of conceptual learning.

While you’ll see their work cited everywhere (see full citation below), it’s virtually impossible to find the actual study.

When I was reading about it to beef up my understanding for this article, I actually used another one of their papers (also cited below).

It’s kind of fun to read those old studies typed out on typewriters with diagrams done with a rule and pen.

It reminds us that effective teaching isn’t about high tech; it’s about high thinking.

? Can you use the Frayer Model Incorrectly?

Yes. Here are some ways to avoid that.

Stick to Concepts

The strength of the Frayer model is in the exploration of concepts.

I see many teachers using it at too basic of a level.

They focus too much on facts and strict definitions, rather than the power of conceptualizing.

Be meta.

Instead of starting with triangle, consider starting with shapes or polygons.

Remember that this is a conceptual model. It works best when we’re looking at concepts rather than specific facts.

Ian Byrd described this well in his article about the Frayer model (which I highly recommend reading).

He says that facts are isolated details, easy to test on multiple-choice exams.

He goes on to explain that, “Concepts are more abstract. They will contain facts and examples. Because they’re abstract, they’re difficult to define. You can’t directly draw a concept, but you could create a symbol.”

Take Time to Introduce the model

Our students are so used to graphic organizers that we may not realize we need to introduce the Frayer Model to them.

We get too caught up in the template and forget that the power is in the analysis.

I suggest doing it first as a whole class activity (see below for different ways to implement the model in your classroom) and then have students complete it independently.

Connect it to text

The Frayer Model should not be a one-off used to look at a term in isolation.

It’s stronger when it’s connected to text or video (or any other way students engage with content).

Don’t just give kids some random concept.

Tie it to reading or viewing or listening.

Keep it (somewhat) complicated

Its best use is with concepts that might be confusing, so don’t overuse with simple vocabulary words (unless you are teaching the Model or the vocabulary word is not that simple!).

It’s not the best use of the Frayer Model to have the word “run” as the concept. Virtually all students understand what it means to run.

Choose concepts they struggle with, concepts easily confused with other concepts, and concepts that you’ve seen cause students problems in the past.

While I’m sharing this on my site that is entirely focused on the teaching of vocabulary, I would advise that you not use this for just any vocabulary word.

Any technique gets old when overused, so save this one for those concepts students really need to explore deeply.

Give students opportunity to verify their thoughts.

After the students have completed their Frayer Model, allow them to verify what they’ve constructed by consulting text.

This isn’t a quiz; it’s an exploration and expansion of knowledge.

Please do not have it be a situation where students have to construct it out nothing and turn it in without confidence in the validity of their ideas.

? Ideas for using the Frayer Model in Class

One of the beautiful things about the Frayer Model is how versatile it is. It can be used in so many ways in class. Here are a few of my favorites.

Whole Class

You can build a Frayer Model with the whole class, having the teacher or a student lead the discussion.

I find that this works well when you have students break apart into smaller groups to brainstorm and bring those ideas back to the group.

The whole-class method works in a virtual environment or an in-person one, so it’s nicely flexible.

Small Group – poster

One of my favorite ways to use a Frayer is to have small groups create a poster. Here’s how to do it:

- Divide class into groups of three.

- Give each group a poster board.

- Have each group explore a concept that is either assigned or chosen.

- Give a minimum number of characteristics (4 is a good number).

- Give a minimum number of examples and non-examples (3 is a good number). One per student.

- Once the posters are complete, either do a gallery walk or have the groups do short presentations on their poster.

Have students write in different color marker so you can tell who did what.

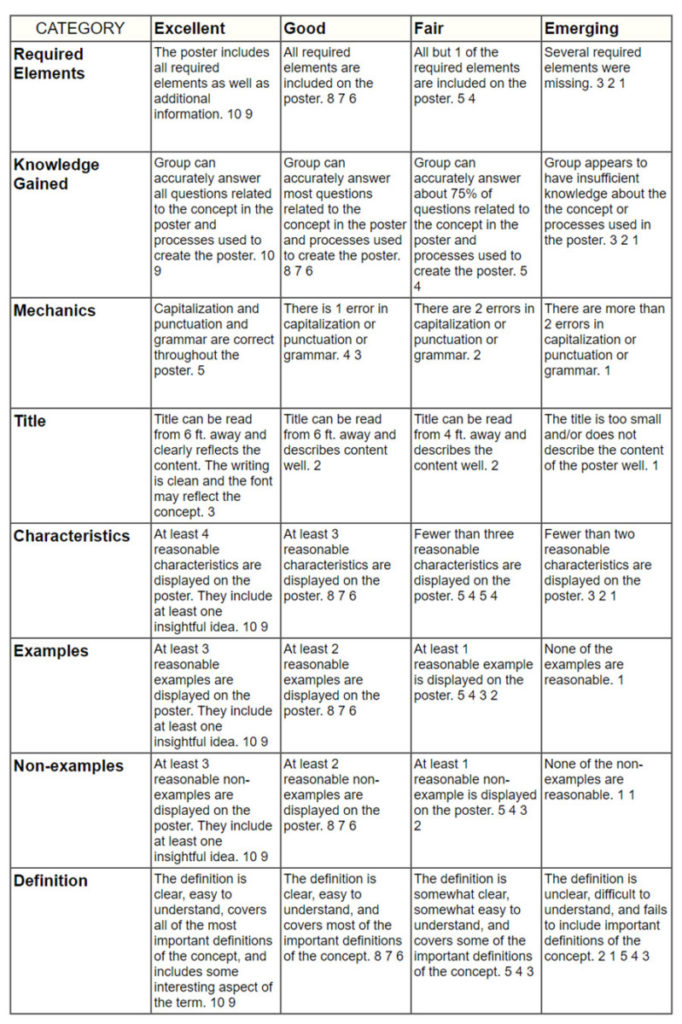

Rubric

When you have a group project, a best practice is to have a separate rubric for the group and the individual.

Here is a rubric for the group for the Frayer Model Poster.

I created in Rubistar and made it available to be edited, so you can adjust it to your own needs/circumstance.

If you want to use this method virtually, have students create their poster in Google Slides, Jamboard, or similar platform.

Small Group – digital

Using the digital template I created (or create your own), have students work in groups in the same slidedeck. If you’re a Google class, you can use Google Slides. If not, use whatever platform you use.

Add one slide per group and have the groups list the members in the notes section of the slide.

Small group – puzzle model

Put students in groups of three and give each member a specific part of the Frayer Model template.

One student provides characteristics, one examples, one non-examples, and then the group crafts a definition together.

If you’re doing this in an in-person environment, it works well to print two copies of the template, cut one apart, and then have students paste their sections on the intact template in the correct section.

Virtually, simply have the students indicate which section of the template they filled out.

Individual – online

Individuals can complete the digital template.

To do this, my suggestion would be to push out the template to each student and then collect them into a single slide show after they are completed.

There are some variations within this:

- All students work on the same concept

- All students work on different concepts

- A number of concepts are divided up among the students, with perhaps four or five students working on the same concept

Backwards Partner

In this version, the teacher gives students a concept and they create a Frayer model for it, leaving off the term.

They exchange their graphic organizer with another student and they try to guess the concept and/or augment the graphic organizer.

Make a one-word summary

After the graphic organizer has been completed, have students come up with a one-word summary of the concept.

Make a hashtag

After students have completed a graphic organizer of the concept, have them come up with a hashtag for the concept. Gather several from the class.

? Differentiation

For advanced learners, consider substituting subordinate concept for example, and superordinate concept for non-example.

Here’s an example of what that looks like:

Concept: Mammal

Subordinate concepts: marsupial, monotremes, placentals

Superordinate concepts: animals, vertebrates, biological life forms

The first alternate version of the Frayer Model (essential/non-essential characteristics) is a nice differentiation opportunity for highly-able learners.

Rather than looking at all characteristics holistically, they further categorize by essential/non-essential characteristics.

To support learners who need extra help, consider giving possible examples/non-examples.

These should not all be correct. They should be choices from which to select.

? Wrapping Up:

The purpose of the Frayer model is to help students learn to identify and define unfamiliar concepts and vocabulary.

As students describe the characteristics of a concept and select examples and non-examples, they will be better able to construct an accurate definition.

It helps students understand concepts within the larger context of the text or content they are exploring, and it asks them to go beyond memorizing definitions to synthesis of their prior learning.

As you move away from just using the Frayer Model template as just any ol’ graphic organizer and really harness its power, you’ll see your students gain important insight and understanding of key concepts.?

Citations:

Bergland, Roberta & Johns, Jerry. Strategies for content area learning: Vocabulary comprehension response. Dubuque, IA: Kendall/Hunt Pub.

Buehl, Doug. Classroom strategies for Interactive Learning, 4th edition. Stenhouse Publishers.

Byrd, Ian. Fully explain concepts with the Frayer Model.

Frayer, D.A., Frederick, W.C., & Klausmeier, H.J. (1969). A schema for testing the level of concept mastery; Report form the project on situational variables and efficiency of concept learning. Madison, WI: Wisconsin Research and Development Center for Cognitive Learning.

Klausmeier, Herbert J. & Frayer, Dorothy A. Cognitive Operations in Concept Learning. Wisconsin Univ., Wisconsin Research and Development Center for Learning. Report No. 36. (Access it here.)